剑桥雅思5:Test2雅思阅读PASSAGE 3真题+答案+解析

发布时间:2020-09-25 关键词:剑桥雅思5:Test2雅思阅读PASSAGE 3真题+答案+解析为了帮助大家在雅思考试中取得的成绩,下面新航道小编为大家整理出关于剑桥雅思5:Test2雅思阅读PASSAGE 3真题+答案+解析,大家可以多加练习。

TEST 2 PASSAGE 3 参考译文:

The Birth of Scientific English

World science is dominated today by a small number of languages, including Japanese, German and French, but it is English which is probably the most popular global language of science. This is not just because of the importance of English-speaking countries such as the USA in scientific research; the scientists of many non-English-speaking countries find that they need to write their research papers in English to reach a wide international audience. Given the prominence of scientific English today, it may seem surprising that no one really knew how to write science in English before the 17th century. Before that, Latin was regarded as the lingua franca1 for European intellectuals.

The European Renaissance (c. 14th-16th century) is sometimes called the ‘revival of learning’, a time of renewed interest in the ‘lost knowledge’ of classical times. At the same time, however, scholars also began to test and extend this knowledge. The emergent nation states of Europe developed competitive interests in world exploration and the development of trade. Such expansion, which was to take the English language west to America and east to India, was supported by scientific developments such as the discovery of magnetism and hence the invention of the compass improvements in cartography and — perhaps the most important scientific revolution of them all — the new theories of astronomy and the movement of the Earth in relation to the planets and stars, developed by Copernicus (1473-1543).

England was one of the first countries where scientists adopted and publicised Copernican ideas with enthusiasm. Some of these scholars, including two with interests in language — John Wallis and John Wilkins — helped found the Royal Society in 1660 in order to promote empirical scientific research.

Across Europe similar academies and societies arose, creating new national traditions of science. In the initial stages of the scientific revolution, most publications in the national languages were popular works, encyclopaedias, educational textbooks and translations. Original science was not done in English until the second half of the 17th century. For example, Newton published his mathematical treatise, known as the Principia, in Latin, but published his later work on the properties of light — Opticks — in English.

There were several reasons why original science continued to be written in Latin. The first was simply a matter of audience. Latin was suitable for an international audience of scholars, whereas English reached a socially wider, but more local, audience. Hence, popular science was written in English.

A second reason for writing in Latin may, perversely, have been a concern for secrecy. Open publication had dangers in putting into the public domain preliminary ideas which had not yet been fully exploited by their ‘author’. This growing concern about intellectual property rights was a feature of the period — it reflected both the humanist notion of the individual, rational scientist who invents and discovers through private intellectual labour, and the growing connection between original science and commercial exploitation. There was something of a social distinction between ‘scholars and gentlemen’ who understood Latin, and men of trade who lacked a classical education. And in the mid-17th century it was common practice for mathematicians to keep their discoveries and proofs secret, by writing them in cipher, in obscure languages, or in private messages deposited in a sealed box with the Royal Society. Some scientists might have felt more comfortable with Latin precisely because its audience, though international, was socially restricted. Doctors clung the most keenly to Latin as an ‘insider language’.

A third reason why the writing of original science in English was delayed may have been to do with the linguistic inadequacy of English in the early modern period. English was not well equipped to deal with scientific argument. First it lacked the necessary technical vocabulary. Second, it lacked the grammatical resources required to represent the world in an objective and impersonal way, and to discuss the relations, such as cause and effect, that might hold between complex and hypothetical entities.

Fortunately, several members of the Royal Society possessed an interest in Language and became engaged in various linguistic projects. Although a proposal in 1664 to establish a committee for improving the English language came to little, the society’s members did a great deal to foster the publication of science in English and to encourage the development of a suitable writing style. Many members of the Royal Society also published monographs in English. One of the first was by Robert Hooke, the society’s first curator of experiments, who described his experiments with microscopes in Micrographia (1665). This work is largely narrative in style, based on a transcript of oral demonstrations and lectures.

In 1665 a new scientific journal, Philosophical Transactions, was inaugurated. Perhaps the first international English-language scientific journal, it encouraged a new genre of scientific writing, that of short, focused accounts of particular experiments.

The 17th century was thus a formative period in the establishment of scientific English. In the following century much of this momentum was lost as German established itself as the leading European language of science. It is estimated that by the end of the 18th century 401 German scientific journals had been established as opposed to 96 in France and 50 in England. However, in the 19th century scientific English again enjoyed substantial lexical growth as the industrial revolution created the need for new technical vocabulary, and new, specialized, professional societies were instituted to promote and publish in the new disciplines.

科技英语的诞生

虽然当今世界科学为包括日语,德语和法语在内的少数几门语言所统治,但是英语可能才是科学界最普及的世界语言。这不仅仅是由于美国这样的英语在科学研究中所起的重要作用,而且还是因为许多非英语的科学家发现为了拥有广大的国际读者群,他们需要用英语写研究论文。今天,科技英语的地位已经显得重要。因此,你可能很难想到在17世纪之前竟没有人很淸楚在科学写作中如何使用英语,(事实上)在17世纪之前,被人们视为欧洲知识分子通用语言的是拉丁文。

约在14到16世纪间出现的欧洲“文艺复兴”有时被称作是“知识复兴”,在这一时期,人们对失落的古希腊罗马时期的知识重新萌发了兴趣。然而,与此同时,学者们也开始检验和扩展这种知识。欧洲新兴竞相进行世界探险、发展贸易,这些活动的增加,使英语向西传到了美洲,向东传到了印度。这些活动获得了科学进步的支持,如磁场的发现以及由此而发明的指南针,地图制作技术的改进,和其中或许最为重要的科学变革——由哥白尼(1473-1543)创立起来的地球与其他行星和恒星相对运动的理论和天文学的新理论。

英格兰是率先有科学家热情地接受并宣传哥白尼的思想的之一。这些学者当中,有两位对语言感兴趣,他们分别是John Wallis和John Wilkins。1660年,这两位学者帮助组建了英国皇家学会,来推广实证性的科学研究。

整个欧洲大陆上都陆续出现了类似的研究院和协会,从而创立起了新的民族科学传统。在科学革命的初始阶段,大多以本国语言出版的出版物都是大众读物、百科全书、教科书和译著。直到17世纪下半叶,英语才成为原创科学所使用的语言。例如,牛顿发表自己的数学论文《自然哲学的数学原理》时用的是拉丁文,但后来发表他有关光的特性的论文《光学》时,用的却是英文。

原创科学一直使用拉丁文写作有多个原因。首先就是读者的问题。拉丁文适合广大国际学者阅读,而英语虽然可以被社会上的人所理解,但这些读者的是英国国内的读者。因此,大众科学是用英语写就的。

第二个用拉丁文写作的原因或许显得荒谬,那就是想要保守秘密。公开出版著作可能会导致还未被原作者研究透彻的初步理念进人公众领域。对知识产权的日益关注是那个时代的特征,这既反映出一种人文关怀,即对富于理性的科学家个人通过自己的脑力劳动进行发明和发现的关怀,又体现出原创科学与商业化利用间日益紧密的联系。那些懂拉丁文的学者、绅士与没有受过什么正规教育的商人是有社会差异的。17世纪中期的时候,数学家将自己的发现和例证用密码、晦涩的语言来描述,或写成个人的便条,封存在英国皇家学会的小盒子里,以保守秘密,这在当时是司空见惯的事情。有些科学家更愿用拉丁文的原因可能就是因为尽管拉丁文的读者是世界性的,却是有限的,社会上没有多少人懂,医生则对拉丁文万分钟爱,将其视为“内部人的语言”。

原创科学迟迟未用英文书写的第三个原因可能与近代早期英语语言还不发达有关。英语还不能的用于科学说理。首先,英语缺乏必要的技术词汇;其次,英语没有必要的语法,无法客观公正地表现世界,也无法讨论各种关系,如复杂而又是假设性的各实体间可能存在的因果关系。

幸运的是,有几名英国皇家学会的成员对语言感兴趣,并开始从事各种语言学方面的研究工作。尽管1664年关于建立改善英语委员会的提议没有什么结果,但是英国皇家学会的成员却做了大量的工作,促进用英语出版科学著作,鼓励恰当写作风格的形成。许多英国皇家学会的成员也用英文发表了学术专著,首批成员包括学会首任实验管理员罗伯特·胡克,他1665年出版了《显微图集》,书中描述了他的显微镜实验。这本著作以口头讲解示范和讲座的文字记录稿为蓝本,大体上是记叙文风格。

1665年,一份新的科学杂志《哲学汇刊》创刊。这或许算得上是首份英文国际科学期刊。该期刊鼓励新的科学写作风格:简洁、重点地描述某一特定实验。

因此,17世纪算是科技英语形成的发展阶段。在接下来的一个世纪中,科技英语的这种发展势头却消失了,因为德语成为了欧洲科学领域的主导语言。据估计,到了18世纪末,德语科学杂志有401份,与之相对,法语科学杂志有96份,英语科学杂志有50份,尽管如此,到了19世纪,伴随着工业革命对新技术词汇的需要,科技英语在词汇上重新有了大幅度的增长。同时,新的专业学会也纷纷建立起来,促进新学科的发展和著作的出版。

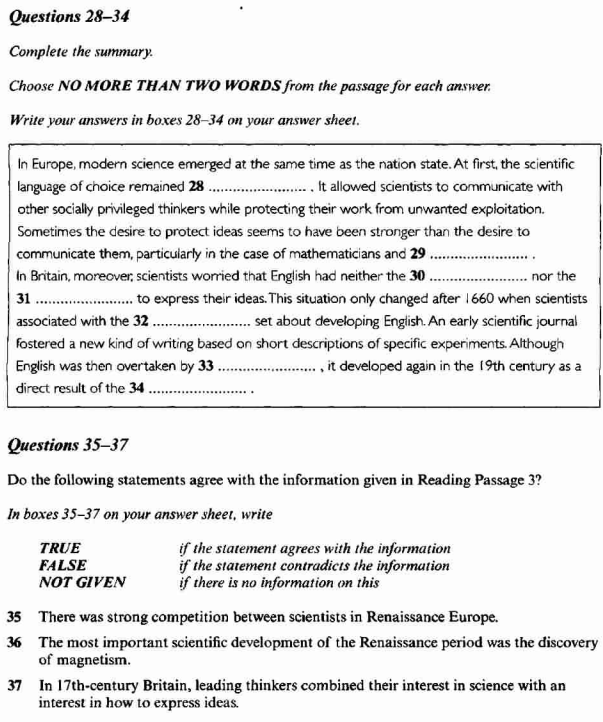

Question 28

答案: Latin

关键词:Europe/nation state/At first

定位原文: 文中第1、5、6段

解题思路: 在首段末句,作者提到了 Before that, Latin was regarded as the lingua franca for European intellectuals. 我们隐约可以感觉到拉丁文在学术界的盛行,但这还不足以让我们确定此空就要填Latin一词。在第五和第六段中,作者提到了学术界流行拉丁文的原因。其中第六段开头一句提到A second reason for writing in Latin may, perversely, have a concern for secrecy. 这正好就等同题目中28空后面的那句话,所以我们椎测答案应该填写Latin一词。

Question 29

答案: doctors

关键词: Mathematicians

定位原文: 第6段中最后3句

解题思路: 题目中告诉我们:有的时候保护个人观点的欲望远远大于与人分享观点的欲望,特别是对于数学家和___。在这里应该填上一个表示职业的名词。而第六段中在mathematician之后,只有一个表示职业的名词,那就是doctors。故答案应该填 doctors。

Question 30 and Question 31

答案: technical vocabulary grammatical resources (in either order)

关键词: Britain/ English/ neither... nor...

定位原文: 第7段第3句“First, it lacked…”

解题思路: 首先用English将此题定位在第七段中,这一段提到了英文为什么迟迟未被用作学术语言的原因。从题目上我们看出这两个原因应该是并列的,进而找到了first和second,然后就选出了答案technical vocabulary和grammatical resources。

Question 32

答案: Royal Society

关键词:after 1660/ associated with

定位原文: 第8段第1句“... Several members of the Royal Society... ”

解题思路: 按照顺序原则,此题答案应该在第八段出现。在这一段当中作者不断提到皇家学会的科学家如何致力于发展英语作为一种学术语言,并且举出了具体的例子。所以答案应该填Royal Society。

Question 33

答案: German

关键词:journal/English/overtaken

定位原文: 第10段第2句“...as German established itself as…”

解题思路: 第十段中提到德语压倒英语成为主要的科学语言。establish...as...确立为……。

Question 34

答案: industrial revolution

关键词:19th century

定位原文: 第10段最后1句

解题思路: 是工业革命促进了科技英语的复兴,所以此题答案应该填industrial revolution。

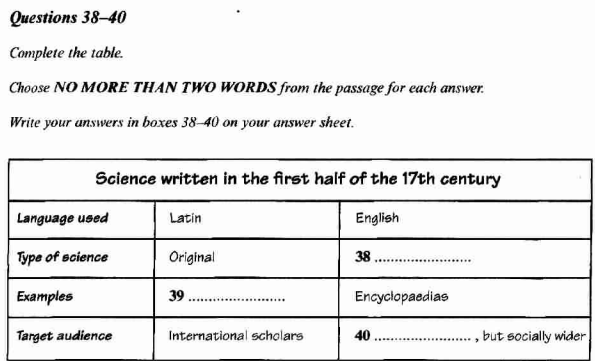

Question 35

答案: NOT GIVEN

关键词:Renaissance Europe

定位原文: 第2段内容

解题思路: 在此段当中并没有提到文艺复兴时期欧洲的科学家们是如何激烈竞争的,是一道完全未提及型NOT GIVEN。

Question 36

答案:FALSE

关键词:magnetism

定位原文: 第2段第4句“ ...was supported by scientific developments such as the discovery of magnetism, improvements…”

解题思路: 这句话表明文艺复兴时期最重大的发现也许是天文学方面的新理论,这就和题目当中磁场的发现相抵触了,故应该选择FALSE。

剑桥雅思5Test2阅读答案解析及解题思路指导Question 37

答案:TRUE

关键词:17th-century Britain

定位原文: 第3段内容

解题思路: 根据T/F/NG题目一般每段考査一题、按顺序出题的原则,我们将这道题目定位在第三段,而England一词也印证了我们的定位。但是如果想在这一段直接找到与题目相对应的词语却困难。本段只是描到英格兰是率先有科学家热情地接受并宣传哥白尼的思想的统一。这些学者当中,有两位对语言感兴趣,他们分别是1660年,这两位学者帮助组建了英国皇家学会,来推广实证性的科学研究。所以我们可以推断出本题目为TRUE。

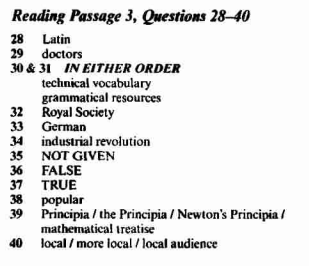

Question 38

答案: popular

关键词:original

定位原文: 第5段最后1句

解题思路: 此处要填一个与original相对的词,故popular最合适。

Question 39

答案: Principia

关键词: encyclopedia

定位原文: 第4段最后1句

解题思路: 通过旁边的纵栏我们了解到英文是用来书写大百科全书的,而横栏又告诉我们此处需要一个例子,于是我们需要填写的就是用拉丁文书写的一个范例,所以填Principia。

Question 40

答案: local

关键词:audience

定位原文: 第5段第3句

解题思路: 通过横栏的audience一词我们找到了第五段。拉丁文的目标读者是国际学者,而英文的目标读者则更广泛,也更本地化。